I have always been a baseball fan and, in the course of my guidebook-writing career in the Southern Cone countries, I would often say that I left home when the World Series ended and returned for Opening Day. This wasn’t quite literally true, but it did mean that I had something to occupy my time in the Northern Hemisphere when nothing was happening on the diamond (a truly appropriate description of any baseball field, including this unexpected gem in the Argentine city of Salta).

|

| The Argentine city of Salta has a new baseball stadium, but this older diamond was still a gem. |

In mid-1981, when my wife first arrived in the United States from Argentina—a country in which baseball is still a fringe sport—she immediately took to Fernando Valenzuela, the Los Angeles Dodgers’ Mexican pitcher who served as a symbol of inclusion in her new home country. It helped, of course, that I was a Dodgers fan since my childhood—since the early Jackie Robinson years—and we have maintained that loyalty toward what has long been baseball’s most admirable franchise. By signing Robinson, the Dodgers had led the way in crossing the “color line” that had excluded black players from Major League Baseball.

|

| Dodger Stadium, where the legendary Fernando Valenzuela began his career. |

That progress, however, hasn’t been without setbacks. The Dodgers won the World Series in 2024, and that victory came with an invitation to visit the White House that has been traditional since 1924. Many of us hoped that the team would decline the invitation to interact with an occupant (who shall remain nameless here) whose loathsome public persona, including overt racism, was unpleasant at best. Then, however, we could at least rationalize that the visit was part of a longstanding apolitical tradition.

|

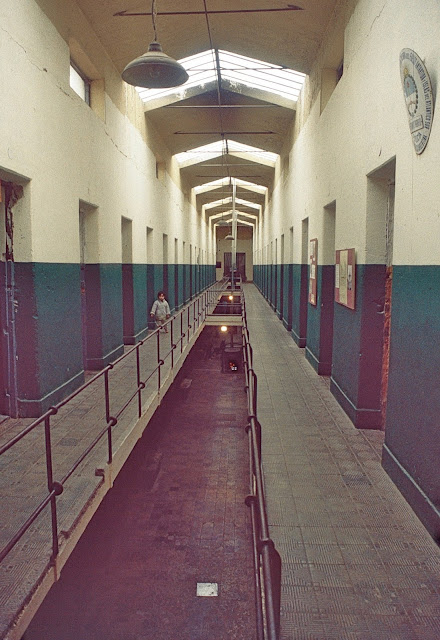

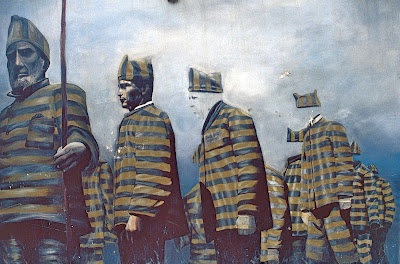

| Argentina's military dictatorship kidnapped and murdered my future brother-in-law's first wife in 1976. |

That rationalization is no longer tenable, if it ever was. It’s truly disheartening, in face of this regime’s assault on civil liberties—resorting to widespread kidnapping, prison camps, and even summary public executions—to think that the Dodgers would once again honor the current occupant with their presence. It’s worth adding here that my future brother-in-law’s first wife, María Eugenia Sanllorenti, was kidnapped in the Argentine city of La Plata and then murdered. It was more than three decades before forensic experts identified her remains.

|

| The Argentine dictatorship abducted Maru from this apartment in the city of La Plata in 1976. |

The last straw, here, should be the White House’s grotesque caricature of former President Barack Obama (this country’s first black President) and his wife Michelle as apes in the jungle. What would Jackie Robinson say? Perhaps someone in the Dodgers ownership should ask Rachel Robinson, Jackie’s 103-year-old widow and head of the Jackie Robinson Foundation, her opinion.

At the very least, the Dodgers could decline the invitation with a statement saying “We did that last year, thank you.” Then we could wholeheartedly cheer for the Dodgers’ third consecutive championship—a three-peat—in 2026.

Should the Dodgers decline the invitation, they could face backlash from a vengeful White House that went ballistic over Bad Bunny's Super Bowl half-time show, which celebrated the culture of Puerto Rico—a territory whose inhabitants are US citizens—and other Latin American peoples. There's at least one Dodger who would almost certainly boycott an invitation—the charismatic utility infielder/outfielder Enrique (Kiké) Hernández is a Boricua who was an enthusiastic presence at Sunday's game and halftime show. Relief pitcher Edwin Díaz is also Puerto Rican.

As US citizens, both of them would have little to risk by declining the invitation. However, the Dodgers also have players from Cuba, the Dominican Republic Venezuela, Japan, and South Korea who could conceivably have their work visas revoked by a vengeful White House. There are many more in the Dodgers' minor league system, so this could wreak true havoc.

Post-Script: I just realized this is my first blog entry in more than three years. I'm not traveling quite so much now, though there is a new edition of Moon Handbooks Patagonia, and I'll try offer my insights a bit more frequently.

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)