Since arriving in Chile, I’ve had four occasions to change money—thrice at ATMs and once over the counter at a casa de cambio (exchange house). Normally in Chile I use an ATM but, in the latter case, I had to pay my mechanic for auto repair that exceeded the Ch$200,000 (about US$225) withdrawal limit for a single transaction.

|

| A casa de cambio in Pucón, Chile |

|

| A BancoEstado ATM (also in Pucón) |

Using the ATM here still makes sense, but there are drawbacks as well. In the past, the public BancoEstado made no charge for any withdrawal, but now it collects Ch$5500 (about US$6) per transaction, amounting to a 2.75 percent fee. Later, out of curiosity (and necessity), I made a similar withdrawal from the private Banco Itaú and incurred a charge of CH$6000 (almost US$7, or 3 percent). I rather assumed that would be the private bank standard but I was mistaken—at a Banco de Chile machine, I paid Ch$8500 (nearly US$10, 4.25 percent).

Thus, BancoEstado remains my default option but, in most places, private bank machines are far more abundant. The exception is very small towns, where BancoEstado is often the only option, and that’s fine with me.

Meanwhile, there’s been another development in Chilean travel, and that has to do with credit card surcharges. Since I arrived in the country, I have experienced multiple purchases with a small additional charge for paying with a foreign credit card. Yesterday morning, for instance, my Ch$9000 breakfast (about US$10) came with a surcharge of Ch$328 (3.6 percent). There seems to be no consistency on this, however, and at least half my purchases have had no additional charge whatsoever. Still, visitors should be prepared for this.

Meanwhile, in Argentina…

The Dólar Blue is nearly double the official rate.

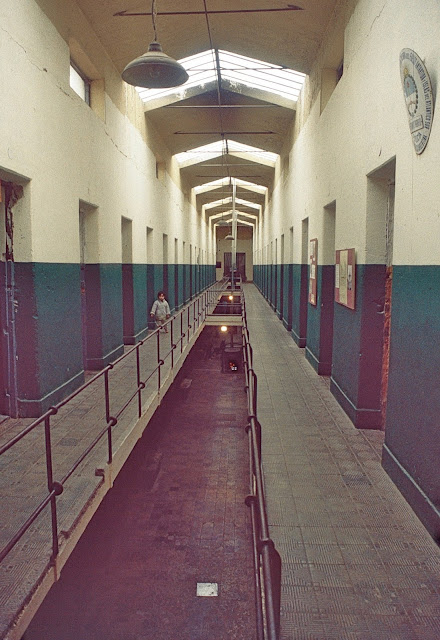

For several years now, one of the hassles of traveling in Argentina has been the multiplicity of exchange rates, and the necessity to carry large amounts of US cash to exchange at the “blue dollar” rate (that’s a euphemism for black market, which is widely accepted). Even with the more favorable blue rate, visitors have to carry large numbers of Argentine banknotes, because the highest value is just 1000 pesos (about US$3 at the blue rate).

Now, however, there’s been a step in the right direction, as the government recently instituted the “Dólar MEP,” which stands for Mercado Electrónico de Pagos (Electronic Payment Market). What this means is that visitors, when paying for good or services with a foreign credit card, will benefit from the blue rate rather than the official exchange rate but, according to a Bariloche friend who operates an adventure tourism agency, the situation isn’t perfect.

|

| A cueva near our apartment in Palermo, Buenos Aires |

That’s because many Argentine businesses still prefer to deal in cash, and that means visiting so-called cuevas, informal exchange houses that operate with official tolerance (though not approval). It’s also because, as yet, it’s not clear whether or not the the Dólar MEP applies to ATM transactions—will visitors still get the official and disadvangeous exchange rate when withdrawing cash from local banks? Stay tuned.

|

| This Western Union office also serves as a cueva, and you go to the front of the line. |

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)

.jpeg)