Over more than four decades, I’ve visited the city of Ushuaia at least a dozen times—first, in 1979, when Argentina had nearly provoked a potentially ruinous war with Chile over three small islands in the Beagle Channel. At the tip of the South American continent, Tierra del Fuego had long had a reputation as the “uttermost part of the Earth” but, with only about 11,000 people, Ushuaia then was nothing like the Antarctic cruise ship capital it is today.

At that time, about to enter grad school at Berkeley, I had only a general understanding of the area’s lengthy penal history and, given Argentina’s brutal military dictatorship, poking around places like the former Presidio Nacional (National Prison)—then under naval control—was inadvisable. It’s this history, and related developments, that Ryan C. Edwards explores in A Carceral Ecology: Ushuaia and the History of Landscape and Punishment in Argentina, recently published by the University of California Press.

.jpeg) |

| Ushuaia has always enjoyed an imposing setting, but it was once a rugged frontier outpost. |

In 1884 Argentina initially established a lighthouse and military prison at Isla de los Estados (Staten Island), a rugged offshore island at the eastern tip of Tierra del Fuego, but the extreme climate—incessant winds, rain, and snow—dictated its abandonment for a site on the big island’s southern shore in 1902. What is now the city of Ushuaia had been a rather less rugged encampment of British missionaries and Argentine gold-seekers for decades before that.

.jpeg) |

| There's now a national park footpath to the Chilean border (though it's formally illegal to cross). |

By some accounts, Ushuaia was nevertheless a “natural prison” from which escape was nearly impossible. The Isla Grande de Tierra was then a roadless wilderness—even though the Chilean border was technically within walking distance—surrounded by violent seas (Anarchist Simón Radowitzky, who assassinated Buenos Aires police chief Ramón Falcón 1909, did make a valiant escape attempt). Still, the Argentine government built a solid prison to confine its convicts—or did it?

.jpeg) |

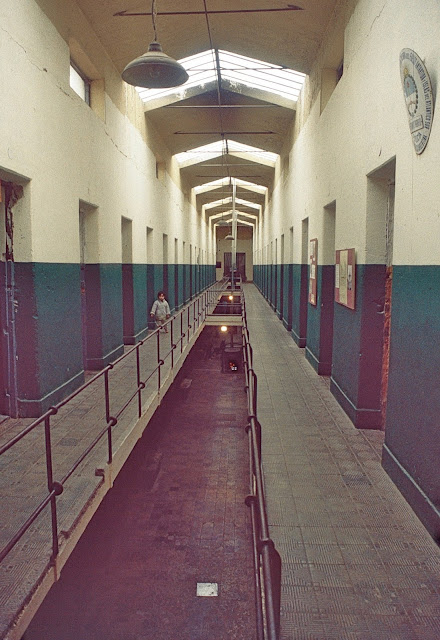

| Cellblocks of the former prison (now the Museo Marítimo) |

The prison, which closed in 1947 but reopened as a museum 50 years later, took its architectural inspiration from Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary. Of an initial plan of eight radial cellblocks, only five were completed and it was, in fact, a “prison without walls,” many of whose inmates worked in and for the community. There were violent criminals, such as the serial killer Cayetano Santos Godino, who were confined to small cells, but many others worked on outside projects—some of them dangerous, such as logging in the forests that would eventually become Parque Nacional Tierra del Fuego. Others were confinados (political prisoners), such as journalist Ricardo Rojas, who enjoyed “off-campus” housing and could meet with his colleagues away from penal supervision, could purchase better rations, and could even publish accounts of their internal exile in the “Siberia of Argentina.”

|

| Inside the cellblocks |

.jpeg) |

| Originally built for timber extraction, the restored railway is now a tourist attraction at the national park. |

The prison closed when a consensus developed that Ushuaia’s extreme environment, in a thinly populated area, was not conducive to reintegrating prisoners into society. That said, it was the prisoners whose labor, including building a short-line railway for timber extraction, laid the foundation for what is now the national park in a city that has also become the gateway to Antarctica for a growing fleet of international cruise ships.

|

| The port of Ushuaia is now the gateway to Antarctica for cruise ships. |

The prison facilities themselves became a naval base but, as a museum, they’re a visible part of what’s become known internationally as “dark tourism” that also includes similar sights/sites as California’s Alcatraz Island and South Africa’s Robben Island. Again, when I first visited in 1979, this was still to come. The story of how it came to be is engrossing.

|

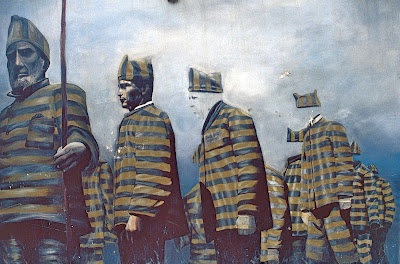

| This mural of prisoners in Ushuaia is a reality check on what it was like in penal days. |

If I have one quibble about this book it’s that, despite the fact that the author was an undergraduate in the Department of Geography at Berkeley, he seems unaware that the author of this review (a Berkeley PhD) had written about Ushuaia in a multitude of guidebooks for various publishers over the last four decades. While I wouldn’t suggest that I have greater insights on the city and its history than his exhaustive research in both primary and secondary sources, an analysis of guidebooks (not just mine) might have added something to the topic of tourism.

No comments:

Post a Comment