Last Monday, having heard that Chilean land borders would close on Wednesday the 18th because of the coronavirus crisis, I drove from San Carlos de Bariloche to Argentina’s Paso Cardenal Samoré border post—where mine was the only vehicle in sight. At a roadside booth, as a young Argentine gendarme (border guard) handed me a ticket to present at immigration and customs, he asked me whether I was suffering any symptoms and, then, he himself sneezed!

|

| With all due respect to Merle and Gabo.. |

In fairness to him, he averted his face and blew into his elbow. When I remarked that he, instead, might have been showing symptoms, he smiled sheepishly and I continued to what might have been the quickest departure ever at what is normally the second-busiest border crossing between the two countries (only the Los Libertadores crossing between Santiago and Mendoza gets more traffic).

|

| Argentina's border post at Paso Cardenal Samoré |

|

| The actual borderline between Argentine and Chile |

|

| Chile's tentative tactic to deal with coronavirus at the border |

On Chile’s side of the border, a handful of vehicles made the process—which included filling out a brief epidemiological questionnaire—slightly slower, but the stroll through immigration, customs and agricultural inspection was still expeditious. Oddly, no official even glanced at the questionnaire, which we had to deposit in a box for presumed data collection. Then I was on my way into Chile, a tale I’ll continue below.

|

| Welcome to Chile! |

How It All Started

This trip has changed dramatically since it began in late February, when I arrived in Santiago with the goal of updating the current 5th edition of Moon Patagonia. On arrival in the capital, my biggest concern was the estallido social (social explosion) protests that—whatever their inconsistencies—have brought decades of social and economic inequality into focus. For the few days I was in town, things were relatively quiet, but there was plenty of evidence of the fierce demonstrations that left several Metro stations and other services in near-ruin (the previous link here reports what stations may be closed at any given time).

|

| Information screens let Metro riders know which stations are closed or with limited access. |

I was staying in the house of Marializ Maldonado, a long-time friend who is working for the constitutional referendum to replace the one drawn by pro-Pinochet ideologue Jaime Guzmán. Guzmán’s custom constitution disproportionately favors Chile’s more conservative elements—rather as gerrymandering favors Republicans in the United States.

|

| Protestors have defaced monuments such as Plaza Baquedano (informally renamed Plaza de la Dignidad). This site has since been cleaned up. |

Marializ hosted several meetings of activists favoring a new constitution, the vote for which was scheduled for April 26th, but has since been postponed until October 25th because of the Coronavirus crisis. Her Revolución Democrática party considers the rowdier elements who’ve gotten the most publicity in the estallido as outsiders (a term they’ve adapted from English).

|

| The Plaza de Armas at Lonquimay features native Araucarias and a knitted tree apparently left over from Xmas. |

When I arrived, the coronavirus issue was not yet critical, and I drove south with the idea that I’d spend two months in Chilean and Argentine Patagonia. That would put me on track to submit a new manuscript toward year’s end, and I began with a long drive that took me to Curacautín, at the northern approach to Parque Nacional Conguillío, where I spent a night at the Bavarian-run guest house Andenrose. The next morning I circled the park via the town of Lonquimay and thence to Melipeuco, the park’s southern gateway but, on this occasion, I decided I couldn’t make the detour into the park.

|

| Feeding time at Aurora Austral, for just three of Konrad's 55 huskies |

Instead, I continued to the lakeside town of Villarrica and, after a brief reconnoiter of the town, on to the Aurora Austral husky farm, where another Bavarian expat, Konrad Jakob, offers sledding trips in winter and carting trips in summer with his kennel of 55 huskies and a handful of mixes (full disclosure: I’m a devotee of northern dogs and have recently adopted a rescue husky, after four malamutes and one Akita). I spent two nights in one of Konrad’s cabañas, commuting to Villarrica to update practical information on the city. I only regret that I’ve never seen the area in winter, when I’d love to go mushing.

|

| My cabaña accommodations at Aurora Austral |

On the third day, I headed to Pucón, at the east end of Lago Villarrica, where I stayed at my long-time favorite Hostería Ecole, but there was an issue that aroused anxiety even before coronavirus entered the conversation. Some years ago, Chile fiddled with the regulations for non-residents crossing the border with their own Chilean vehicles. Were I unable to cross with my vehicle, it would be disastrous for my work.

|

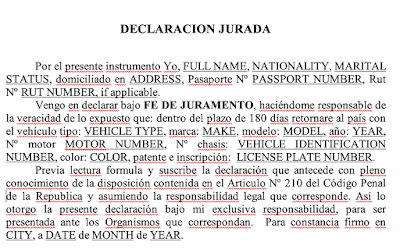

| Template for the declaración jurada that let me cross the border. |

Fortunately, Hans and Verónica Liechti of Pucón’s Travel Aid agency had put me in touch with an American couple who own a house outside town and were in much the same non-resident situation. That couple had found an apparent loophole that allows such vehicle owners to leave the country so long as they obtain a notarized declaración jurada (“sworn declaration”) that they intend to return the vehicle to Chile. They’d done it several times and sent me a template for the document that I completed, printed out, and took to Pucón’s only notary public for verification.

When I Get to the Border…

|

| Loretano is a worthy new Peruvian addition to Pucón's dining scene. |

After three nights in Pucón, where I really enjoyed the new Peruvian restaurant Loretano (presently closed for the virus emergency), I headed east to the border at Mamuil Malal; I couldn’t completely contain my apprehension until, when I produced the declaración jurada, the Chilean customs official gave me a smiling thumbs-up. Entering Argentina was similarly routine, despite the presence of a list of various nationals subject to coronavirus quarantine but not—yet—US citizens. I got in under the wire, as that would happen a couple days later.

|

| At the Mamuil Malal border crossing, Araucarias line the road, which passes through Parque Nacional Lanín. |

|

| Parque Nacional Los Arrayanes was presumably closed to hikers, but there was no visible enforcement at Villa La Angostura. |

The next few days were relatively routine, as I spent a night at Estancia Huechahue, two in San Martín de los Andes, and one in Villa La Angostura, where Argentina’s budding coronavirus precautions became more obvious. En route there had been evidence for concern, as I saw Argentines from a tour bus still sharing yerba mate, and many still greeting each other with kisses on the cheek—men as well as women. Argentina had closed all its national parks, though, and Parque Nacional Los Arrayanes—a popular hiking destination with an entrance in town, was supposedly off-limits (there were still people crossing the line into the park).

|

| Probably now closed because of Argentina's widespread quarantine, the Bariloche tourist office was keeping distance between its personnel and visitors. |

Then I was headed to Bariloche—arguably Argentine Patagonia’s de facto capital, with the notion of continuing south to El Bolsón and Esquel, and then across the broad steppe to Puerto Madryn and Península Valdés. It was not to be, however, as I heard the next morning that Chile was about to close it land borders and, if I did not return before Wednesday, I would be unable to leave (and potentially unable to comply with my declaración jurada).

That information I heard second-hand but, for confirmation, I walked to the Chilean consulate—which was closed. Nevertheless, I rang the bell and, after a middling wait, was assured that US citizens like myself would be able to cross. I left almost immediately, returning via Villa La Angostura and thence to the border crossing described above. Before leaving, though, I managed to visit the new locale of Helados Jauja, arguably Patagonia's best ice creamery (the mother ship is in El Bolsón).

|

| Helados Jauja has new quarters in Bariloche, with a secluded patio in the back. |

When in Chile…

|

| My accommodations at Zapato Amarillo were picturesque, comfortable and - in the current situation - socially remote. |

After crossing the border, I headed to Puerto Octay’s Zapato Amarillo guesthouse, where the Swiss-Chilean couple Armin and Nadia Dübendorfer have hosted me many times over the years. On the outskirts of town, its stylishly rustic cabins were also an ideal place for self-quarantine, with nobody else about. I had considered staying several days, and perhaps even continuing to Puerto Varas, but after Armin and Nadia told me that international flights were being drastically reduced, I took their suggestion to drive to the city of Osorno and reschedule my April 29th departure for California. Otherwise, I would be spending nearly six weeks in Chile in virtual seclusion.

|

| LATAM'S Osorno office switched my flight. It's a nice touch both the agent and the client can watch the computer screen. |

Osorno’s about an hour away, but I was fortunate enough to find parking in the densely built downtown area, barely a block from the surprisingly small LATAM office (Osorno has an airport, but flights are fairly few). There were also few clients, so I quickly got seated and, though my preferred departure date from Santiago on Monday the 23rd was not available, the agent found me space for Tuesday the 24th. She first suggested the route via New York City, then with Delta to SFO, but having heard of huge delays at JFK immigration I chose to fly from Santiago to Mexico City, thence to SFO with Aeroméxico. Time will tell whether I’ve made the right decision, but I’m due home by 1 pm on Wednesday the 25th.

Then there remained the issue of getting back to Santiago, amid rumors there would be a toque de queda (curfew) at midnight. I returned to Puerto Octay immediately and packed my bags for the Chilean capital, a distance of roughly 970 km (about 600 miles) that I covered in 10-1/2 hours, with just two stops to fill the tank (plus some slowdowns for construction). I got to Marializ’s house at 11:30 p.m., just half an hour before the supposed curfew (that’s still not happened, though authorities are encouraging people to stay home). By then, with all apologies to Merle, I'd seen enough white lines for the day.

Here, until Wednesday, I’m in modified self-quarantine, taking short walks around the neighborhood but avoiding contact with anybody—and making minimal purchases from the nearby shop. And writing stuff like this as, for the foreseeable future, we’ve had to suspend work on the new edition of Patagonia.

No comments:

Post a Comment