Recently I dreamt that, having arrived at Buenos Aires’s Aeropuerto Internacional Ministro Pistarini (commonly called “Ezeiza”), I was in a taxi to our apartment in the barrio of Palermo—where my wife and I had been longing to go ever since the pandemic began. En route, though, I realized I’d left the keys at our California home—and then I awoke wondering whether that was a metaphor for the times we’re in. In fact, we’d planned to fly to Argentina this New Year’s Eve, and were eager to see friends and family in and around the Argentine capital, but I’d begun to have my doubts as news of the Omicron variant hit the country especially hard.

|

| We might have hired a taxi here... |

|

| Uki Goñi's Twitter account is a good up-to-date source on many Argentine topics. |

In fact, I’d contemplated postponing the trip a few days earlier, but María Laura was still committed to going until Monday, when she first expressed doubts and then consulted with siblings, nephews, nieces, and friends (some of whom are directly involved in the healthcare system there). Everyone concurred that the situation was worsening, and expressed doubts about the trip despite their eagerness to see us.

|

| Argentina's vax rollout has actually been pretty good, but I couldn't resist posting this photo from my nephew's Parque Patricios neighborhood. |

For our part, we are fully vaccinated and boostered, and live in an area where people take vaccinations and masking seriously, so we were never panic-stricken. That said, we could still theoretically be carriers, and we didn’t want to risk a breakthrough case that could put others at risk. We also worried, however, that flight cancellations and layovers might disrupt the trip—partly because San Francisco International Airport (SFO) is notorious for weather delays and also with respect to our connecting flight in COVID-friendly Texas. That state has great food and music, but deplorable government.

That said, we look forward to trying again in March or so. I might stay a bit longer than the month we originally planned on, as I’m starting to work on the upcoming sixth edition of Moon Patagonia—perhaps an excursion to Ushuaia is in order.

Meanwhile, in Chile…

Chile, of course, will be a key part of the Patagonia update, and its high vaccination rates have made it an example to emulate in handling the pandemic. It’s been circumspect about the entry of non-resident foreigners, though, and that seems likely to complicate the upcoming tourist season, even though more border crossings are opening with Argentina and its other neighbors. Still, there are fairly stringent requirements, including quarantine, and the Chilean bureaucracy has also been slow to acknowledge intending visitors’ vaccination status—according to a friend of mine who’s a permanent resident, a friend of his spent two weeks stranded in Lima because LATAM Airlines would not let him board a connecting flight.

|

| Chile's border are reopening, at least in theory. |

For me, as an independent traveler having to cross the border multiple times while updating my book, frequent retesting and quarantines would mean significant delays and expense. As the attached screenshot shows, that situation may be improving), but requirements are likely to change even more so that southern spring—October or November—seems more agreeable.

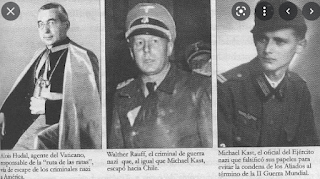

Of course, Chile’s made international headlines for its recent presidential election in which the left-leaning (but hardly extreme) Gabriel Boric defeated right-wing extremist José Antonio Kast (a Pinochet worshipper whose German-born father was literally a Nazi). Though Kast finished first in the multi-candidate primary (there were seven options), the 35-year-old Boric won the runoff handily and, to Kast’s credit, he quickly conceded and congratulated the winner. It’s worth noting that Boric’s final margin was almost identical to that of the 1988 plebiscite that ended Pinochet’s “presidency,” and that Communist candidate Eduardo Artés received only 1.46 percent of the primary vote.

|

| The losing candidate's late father, at right, was literally a Nazi. |

Even so, Kast partisans’ accusations of extremism have continued, the “markets” were not pleased with the result, and the peso has slipped against the US dollar (any visitor so inclined could now eat a Weißwurst more cheaply at the Bavaria restaurant chain that is the basis of the Kast family fortune). Still, as Chile proceeds with a Convención Constitucional to draft a new constitution to replace the Pinochet-friendly document authored by the late rightist lawyer Jaime Guzmán, the challenges to a long overdue reform won’t disappear. The new charter must be approved by plebiscite but until then and even after, governing could be a challenge.

In Other News…

My Patagonia title also includes the Falkland Islands, where I once spent an entire year and have revisited at least half a dozen times. Except for my initial trip, when I flew from and back to the United Kingdom (with a memorable stopover on Ascension Island), I’ve always arrived via the southern Chilean city of Punta Arenas but, since the start of the pandemic, there’ve been no flights on that route, which requires overflying Argentine airspace.

|

| The passenger terminal at the Falklands' Mount Pleasant Airport |

Next year, hopefully, these flights will resume, but the Argentine government (which claims the Islands as the “Malvinas”) has recently stonewalled humanitarian charter flights that would have allowed the Islands’ Chilean residents (there are roughly 200 of them) to return home for the holidays. That’s not an auspicious development.

|

| Alex Olmedo's Waterfront Café is a Chilean-owned business in Stanley. |

For an incisive account of the Islands and their current prosperity, read Larissa MacFarquhar’s outstanding piece in The New Yorker, researched immediately before the pandemic.